In a nondescript London lab in November 2020, a computer accomplished in seconds what evolution perfected over billions of years. DeepMind’s AlphaFold2 predicted protein structures with near-experimental accuracy, solving a 50-year-old grand challenge in biology. The scientific community responded not with measured academic applause, but with genuine awe. Nobel laureate Venki Ramakrishnan called it “a stunning advance.” He wasn’t exaggerating.

Three years later, we’re witnessing the first tremors of a seismic shift. AI-powered protein engineering and synthetic biology aren’t just advancing science—they’re rewriting what biology can be. And unlike previous biotechnology revolutions that promised more than they delivered, this one is already keeping its promises.

The Origami of Life: Why Protein Folding Matters

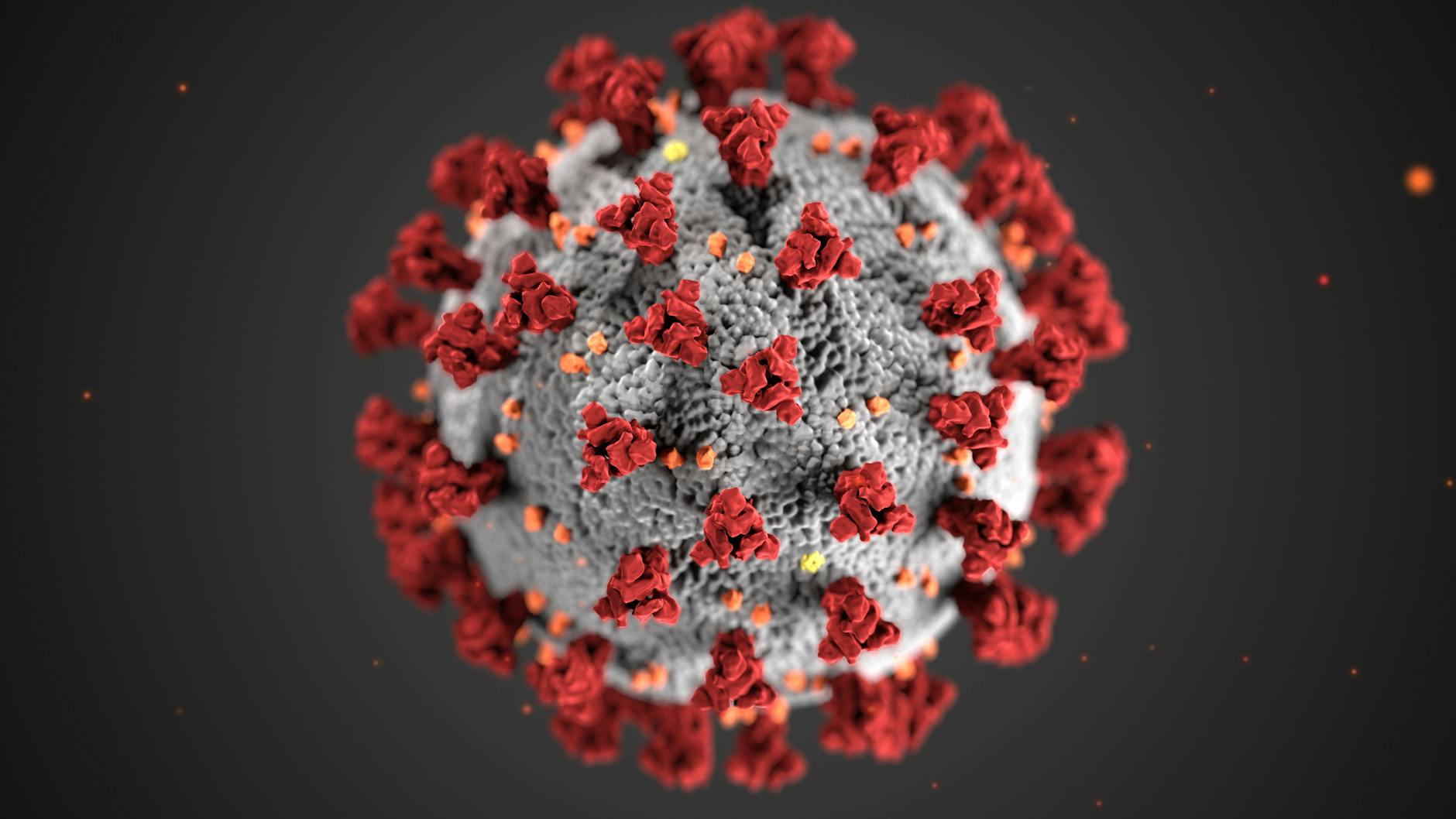

To understand why this matters, we need to grasp what proteins actually do. They are the nanoscale machines that power virtually every process in your body. They digest your food, fight infections, generate energy, and form the structural components of your cells. Their function is determined by their three-dimensional shape—how a linear chain of amino acids folds into complex structures.

For decades, determining these structures required months of painstaking lab work through techniques like X-ray crystallography. Scientists could sequence a protein (identifying its amino acid components) relatively easily, but predicting how that sequence would fold remained computationally infeasible.

“The number of possible configurations a typical protein could adopt is astronomical—more than the number of atoms in the universe,” explains David Baker, director of the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington. “It’s why protein structure prediction was considered AI’s equivalent of going to Mars.”

That impossibility is now yesterday’s problem.

AlphaFold2 solved it using deep learning trained on the Protein Data Bank’s archive of experimentally determined structures. In 2021, DeepMind released the predicted structures for 98.5% of the human proteome. By 2022, they’d published predictions for over 200 million proteins—virtually all known proteins. Work that would have taken centuries now takes hours.

Beyond Prediction: Designing Biology from Scratch

But prediction is just the beginning. The real revolution is in protein design—creating entirely new proteins that have never existed in nature.

At the University of Washington, Baker’s lab has used RoseTTAFold (their AlphaFold-inspired system) to design synthetic proteins with specific functions. In 2022, they unveiled protein “nanomachines” designed to capture toxic chemicals, novel enzymes that catalyze reactions not found in nature, and protein-based vaccines against viruses including influenza and COVID-19.

“We’re no longer limited to the proteins that evolution has given us,” says Baker. “We can design proteins to do things that biology never needed to do.”

Generative AI approaches like ProteinGPT and Chroma are accelerating this further, functioning like “protein language models” that understand the grammar of amino acid sequences. Feed them a desired function, and they can generate candidate sequences likely to perform it.

The implications are staggering: medicine, materials science, energy, and agriculture are all targets for reinvention.

Medicine Reimagined: Drugs That Couldn’t Exist Before

Traditional drug discovery is an expensive gamble with 90% failure rates and decade-long development cycles. AI protein engineering is changing these economics dramatically.

Generata Biotechnology, a startup founded by former DeepMind researchers, recently designed a potential treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in 18 months—a process that typically takes 4-6 years. They used AI to design a protein that specifically targets misfolded SOD1, a protein implicated in some ALS cases.

“These aren’t just marginally better drugs,” explains Daphne Koller, founder of insitro, a machine learning-focused drug discovery company. “They’re drugs that couldn’t have been discovered without these tools.”

The advantages extend beyond speed. AI-designed proteins can:

- Target previously “undruggable” proteins by finding binding sites conventional methods miss

- Create higher specificity, reducing side effects

- Design multispecific drugs that modulate multiple disease targets simultaneously

- Overcome drug resistance by designing against predicted resistance mutations

Companies like Recursion Pharmaceuticals and Genesis Therapeutics are building entire drug discovery pipelines around these capabilities, with dozens of candidates advancing to preclinical testing. Absci recently announced an antibody with 30-fold improved cancer cell killing potency over conventional antibodies.

The FDA approved its first AI-discovered drug in 2022. By 2026, industry analysts project over 30% of drug discovery programs will leverage AI protein engineering—a $50 billion market opportunity.

Synthetic Biology: Programming Life Like Software

While protein engineering focuses on individual molecules, synthetic biology takes a broader approach: treating cells as programmable factories for creating valuable compounds.

Ginkgo Bioworks, a pioneer in this space, uses AI to design microorganisms that produce everything from fragrances to cannabinoids to sustainable materials. Their platform can test thousands of genetic designs in parallel, using machine learning to optimize each iteration.

“Synthetic biology is becoming more like software development,” explains Ginkgo CEO Jason Kelly. “We write the genetic code, test it, debug it, and iterate rapidly.”

This approach is already transforming manufacturing. Traditional chemical synthesis often requires toxic catalysts, extreme temperatures, and petroleum-based feedstocks. Engineered microbes can produce the same compounds using renewable resources at room temperature with minimal waste.

Zymergen (now part of Ginkgo) used this approach to develop a bio-based electronic film that outperforms petroleum-based alternatives for smartphone displays. Moderna used synthetic biology to develop mRNA vaccines in record time. Perfect Day created animal-free dairy proteins identical to those in cow’s milk but produced by engineered yeast.

“We’re moving from a petrochemical economy to a biological one,” says Emily Leproust, CEO of Twist Bioscience, which synthesizes custom DNA for these applications. “Within a decade, we’ll see bio-manufacturing replace traditional methods across multiple industries.”

Environmental Solutions at Planetary Scale

Perhaps the most promising applications address our most urgent planetary challenges.

Joyn Bio, a joint venture between Bayer and Ginkgo, is engineering microbes that help crops fix their own nitrogen, potentially reducing fertilizer use by 30%. LanzaTech captures carbon emissions from steel mills and converts them to ethanol using engineered bacteria. Pivot Bio has developed nitrogen-producing microbes that reduce fertilizer runoff into waterways.

The most ambitious projects target carbon capture. Living Carbon is developing trees with enhanced carbon sequestration abilities. Running Tide is deploying engineered microalgae in the ocean to capture carbon and sequester it in the deep sea.

“Engineered biology may be our best hope for addressing climate change at scale,” argues Jennifer Doudna, Nobel laureate and CRISPR pioneer. “We’re talking about solutions that work with natural systems rather than against them.”

The Risks: Unintended Consequences

Any technology this powerful comes with risks. Synthetic biology capabilities could be misused to create pathogens or disrupt ecosystems. Even well-intentioned applications could have unintended consequences if engineered organisms escape controlled environments.

George Church, professor at Harvard Medical School and synthetic biology pioneer, acknowledges these concerns while advocating for continued development: “The risks are real, but so are the risks of not developing solutions to our most pressing problems. The answer is careful oversight, not abandonment.”

Regulatory frameworks are evolving. The EU’s proposed regulation on AI classifies some biological applications as “high-risk,” requiring rigorous safety assessments. The WHO has published guidance on governance of both AI and genome editing. Industry consortia like the International Gene Synthesis Consortium screen DNA synthesis orders for potential bioweapons.

“We need to move forward carefully but deliberately,” says Alta Charo, bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin. “This isn’t a technology we can afford to develop without public engagement and strong governance.”

Democratization: From Big Labs to Biohackers

While early protein design required supercomputers, tools are rapidly becoming more accessible. Google Colab now offers notebooks that can run protein folding predictions on free GPU instances. Companies like Benchling provide cloud-based tools for designing DNA constructs. Community labs like Genspace in New York offer hands-on synthetic biology education to the public.

This democratization mirrors the evolution of computing from mainframes to personal computers—and may produce similarly transformative innovations.

“The next breakthrough might come from a garage lab in Lagos or a high school student in Bangalore,” says Ellen Jorgensen, co-founder of Genspace. “Biology is becoming a creative medium accessible to anyone with curiosity and basic tools.”

Leading universities are revamping curricula to incorporate these emerging technologies. MIT now offers computational protein design courses to undergraduates. Stanford’s ChEM-H institute brings together chemists, engineers, and medical researchers to train the next generation of synthetic biologists.

The Near Future: 2026 and Beyond

As we approach 2026, several breakthrough innovations appear imminent:

- Programmable living materials: Self-healing concrete infused with engineered bacteria that fix cracks and reduce carbon footprint

- Digital protein therapeutics: Personalized medicine designed for individual patient genetics using AI-optimized proteins

- Cellular computing: Engineered cells that function as biological computers, performing logic operations within the body for precision medicine

- Carbon-negative plastics: Materials produced by engineered organisms that sequester more carbon in production than they release

- Distributed biomanufacturing: Local production of medicines and materials using standardized, engineered organisms

“The 2020s will be for biology what the 1990s were for information technology,” predicts Vijay Pande, general partner at Andreessen Horowitz’s bio fund. “We’re seeing the transition from artisanal to industrial, from discovery to design.”

Evolution 2.0: Biology by Design

For billions of years, evolution proceeded through random mutation and natural selection—a process that produced wonders but was fundamentally unguided. We’ve now entered a new era where biological systems can be designed with purpose.

This doesn’t replace natural evolution but adds a new layer: designed evolution, guided by human intention and accelerated by artificial intelligence. It’s less a hijacking of nature’s methods than an extension of them—giving evolution new tools and directions.

“We’re not replacing nature,” reflects David Baker. “We’re learning its language and expanding what it can create.”

The most profound changes may be philosophical. For millennia, humans have asked what life is. Now we’re learning to write new answers to that question, one amino acid at a time.

As AI and synthetic biology continue their convergence, the boundary between designed and evolved, between synthetic and natural, grows increasingly permeable. We’re not just understanding life’s code—we’re developing new dialects and writing original stories with it.

This is more than a scientific revolution. It’s an expansion of what biology can be and what we can create with it. And it’s happening right now.