On December 5, 2022, scientists at the National Ignition Facility achieved something that had eluded researchers for 70 years: they produced more energy from a fusion reaction than they put in. The margin was tiny—about 50% more energy out than in—and the total energy gain remains negative when accounting for the laser system’s efficiency. But it proved fusion ignition was possible.

That milestone felt distant from practical power generation. Two years later, in 2026, the situation looks dramatically different.

Multiple fusion approaches are converging on practical power generation simultaneously. Private companies backed by billions in investment are building demonstration plants. Established energy companies are forming partnerships to prepare for commercialization. And the underlying technology is advancing faster than the most optimistic predictions from five years ago.

Fusion energy’s breakthrough moment isn’t a single achievement. It’s the convergence of multiple technical approaches maturing simultaneously, backed by unprecedented investment and engineering talent.

Why Fusion Matters

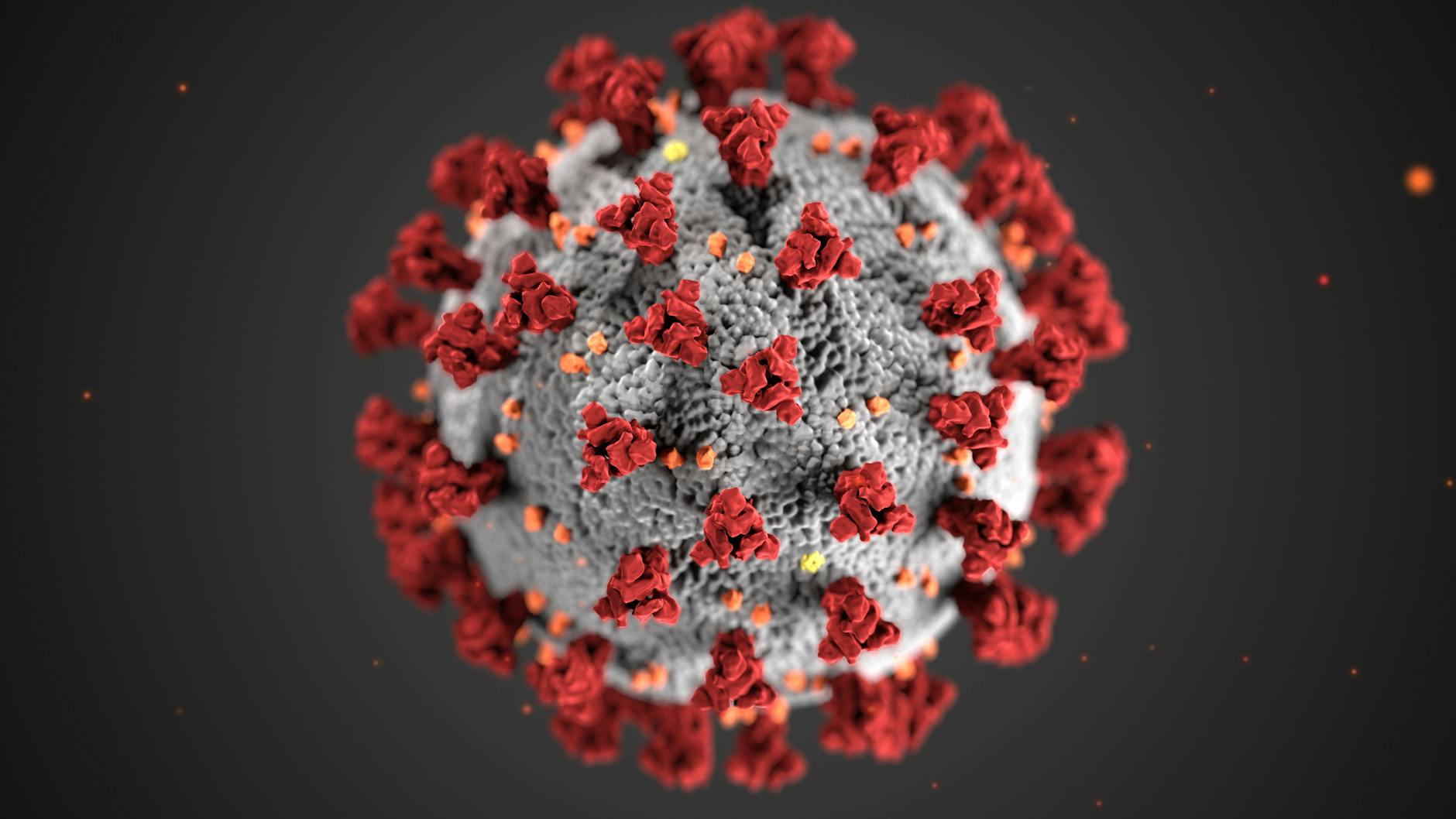

Fusion power promises baseload energy generation without greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, or long-lived radioactive waste. Unlike fission reactors that split heavy atoms, fusion combines light atoms—typically hydrogen isotopes—releasing energy in the process.

The physics works. The sun proves fusion at scale is possible. But recreating solar conditions on Earth requires temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees Celsius—hotter than the sun’s core—while confining plasma long enough for fusion reactions to occur and extracting more energy than the confinement requires.

These challenges have made fusion power the perpetual “30 years away” technology. That timeline is compressing rapidly.

The Technologies Converging

Three main approaches are racing toward practical fusion power:

Magnetic Confinement: The Established Path

Magnetic confinement uses powerful magnetic fields to contain plasma in toroidal (donut-shaped) chambers. The tokamak design, pioneered in the Soviet Union, has dominated research for decades.

ITER, the massive international fusion experiment under construction in France, represents the culmination of this approach. When complete, it aims to produce 500 megawatts of fusion power from 50 megawatts of input—a tenfold energy gain.

But ITER’s multi-decade construction timeline and $20+ billion cost exemplify why fusion has seemed perpetually distant. Private companies are pursuing faster, cheaper approaches.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), an MIT spinout, is building SPARC—a tokamak using high-temperature superconducting magnets that enable much smaller reactors. Where ITER will be 800 tons, SPARC weighs under 1,000 tons and fits in a single building.

“High-temperature superconductors are the game-changer,” explains Dr. Bob Mumgaard, CEO of CFS. “They allow magnetic fields twice as strong as ITER’s, which means plasma pressure—and fusion power—can be 16 times higher in a device half the size.”

CFS plans to demonstrate net energy gain with SPARC by 2025, then build ARC—a 200-megawatt pilot plant by the early 2030s. The company has raised over $2 billion and employs 350 people, applying startup velocity to fusion engineering.

Inertial Confinement: The Laser Approach

The National Ignition Facility’s achievement used inertial confinement fusion: powerful lasers compress a tiny fuel pellet to fusion conditions for a brief moment. While NIF’s success was revolutionary for science, the approach faces major engineering challenges for power generation.

Each NIF shot requires hours of laser preparation and yields barely more energy than the lasers consumed—nowhere near enough to run a practical power plant. But private companies see pathways to dramatic improvement.

First Light Fusion in the UK is pursuing a simplified approach using projectile impact rather than lasers. By firing projectiles at specially designed targets, they achieve fusion conditions without the complex laser systems NIF requires. Their approach potentially offers higher repetition rates and lower costs.

NIF’s success opened funding and talent floodgates for inertial fusion companies. The question isn’t whether the physics works—it demonstrably does—but whether engineering can make it practical and affordable.

Alternative Concepts: The Dark Horses

Beyond mainstream tokamak and inertial approaches, several alternative fusion concepts are advancing:

TAE Technologies has raised over $1.2 billion to develop a beam-driven field-reversed configuration. Unlike tokamaks, their reactor doesn’t require radioactive tritium fuel, using ordinary hydrogen and boron instead. This dramatically simplifies fueling and reduces neutron production, potentially enabling simpler plant designs.

Helion Energy pursues a pulsed, non-ignition approach using D-He3 fuel. Their system creates fusion pulses in a linear configuration, then directly captures energy as electricity without thermal conversion. CEO David Kirtley calls it “the most efficient path from fusion to electricity.”

Both companies have demonstrated key physics principles and are building scaled-up prototypes. Neither has achieved net energy gain yet, but both claim pathways to practical power generation this decade.

What Changed: The Acceleration Factors

Why is fusion progress accelerating now after decades of incremental advances?

Materials and Manufacturing

High-temperature superconductors, developed in the 2000s but only recently manufactured at scale, enable stronger magnetic fields in smaller, cheaper magnets. Modern materials science provides better plasma-facing materials that withstand the extreme conditions inside fusion reactors.

Advanced manufacturing techniques—including 3D printing of complex components and automated assembly—reduce construction time and costs. Where ITER requires artisan fabrication of one-off components, newer fusion reactors use scaled manufacturing approaches.

Computational Tools

Fusion reactor design relies heavily on simulation. Modern supercomputing and machine learning enable optimization impossible 10 years ago. Engineers can test thousands of design variants virtually, dramatically accelerating development.

TAE Technologies uses Google Cloud computing and proprietary machine learning to optimize their reactor designs. “We’re running the equivalent of thousands of experimental shots per day in simulation,” explains CTO Michl Binderbauer. “That accelerates learning by orders of magnitude.”

Private Investment

Fusion research historically depended on government funding, with associated political uncertainty and long timelines. Since 2020, over $5 billion in private capital has flowed into fusion startups.

This private funding enables faster iteration, risk-taking on alternative approaches, and engineering talent at startup velocity rather than national lab pace. Companies can pursue aggressive timelines impossible in government programs.

Energy Transition Urgency

Climate change created unprecedented demand for carbon-free baseload power. Solar and wind are deployed rapidly, but intermittency requires grid-scale storage or complementary baseload generation. Fusion addresses this need.

Major energy companies are paying attention. Chevron invested in fusion startup Zap Energy. Equinor partnered with Commonwealth Fusion Systems. Energy incumbents see fusion as strategic for a carbon-constrained future.

The 2026 Landscape

Multiple fusion demonstration plants are under construction:

- Commonwealth Fusion Systems’ SPARC: Targeting net energy gain by 2025

- TAE Technologies’ Copernicus: Fifth-generation prototype demonstrating key physics

- Helion’s Polaris: Sixth-generation system aiming for electricity generation

- ITER: Under construction but delayed to 2030s operation

Regulatory frameworks are developing. The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission is establishing fusion-specific regulations distinct from fission rules. The UK is creating a simplified pathway for fusion licensing.

Government programs are complementing private efforts. The US Department of Energy launched a $50 million program to accelerate fusion commercialization. The UK committed £220 million to STEP—a pilot fusion plant targeting 2040 operation.

Remaining Challenges

Despite progress, significant challenges remain before fusion power becomes commercially viable:

Materials degradation. Plasma-facing materials endure neutron bombardment and extreme heat. Long-term material performance remains unproven at commercial scales.

Tritium breeding. Most fusion designs use tritium, a rare radioactive hydrogen isotope. Commercial plants must breed their own tritium from lithium blankets surrounding the reactor—a technically challenging requirement.

Economic competitiveness. Fusion plants must compete economically with rapidly improving solar, wind, and batteries. Early fusion power will likely be expensive. Costs must decrease through learning curves similar to other energy technologies.

Engineering at scale. Fusion demonstrations are one thing. Operating reliable power plants 24/7 for decades is another. The transition from prototype to commercial product remains to be proven.

What Success Looks Like

If current progress continues, fusion power plants could begin delivering electricity to grids in the 2030s. Early plants will be expensive and partially demonstration projects. But they’ll prove commercial viability and establish supply chains.

By the 2040s, fusion could provide significant baseload carbon-free power, complementing solar and wind. The theoretical fuel abundance—deuterium extracted from seawater and lithium from the Earth’s crust—could power civilization for millennia.

The transformation won’t be instant. But for the first time, fusion power’s timeline is measured in years and decades, not “always 30 years away.”

The breakthrough isn’t a single achievement. It’s the convergence of materials, computing, investment, and engineering talent finally matching the challenge’s scale.

Fusion energy is transitioning from physics experiment to engineering problem. That’s the breakthrough that matters most.